The National Gallery’s New Show Struggles to Highlight Freud’s Genius

How does one present a fresh perspective on an artist as iconic as Lucian Freud? With multiple exhibitions already dedicated to him, including one at the Royal Academy in 2019 and at Tate Liverpool just last year, the question arises: can we truly see him differently? The National Gallery’s latest exhibition, Lucian Freud: New Perspectives, attempts to answer this by breaking away from established interpretations, trying to reveal Freud beyond his well-known persona as a tortured genius. However, it’s clear that this effort doesn’t quite serve the artist in the way it intended.

Curator Daniel Herrmann’s mission was to detach Freud from the myths surrounding him, a daunting task considering how ingrained those myths are, both in his biography and the prevailing critiques of his work. The exhibition focuses less on the relationships between Freud and his sitters and more on the paintings themselves, urging visitors to engage with them directly, as objects rather than stories.

This approach, however, is complicated by the unforgiving context in which Freud’s work is presented—the National Gallery. Although Freud’s own works aren’t juxtaposed directly with the Old Masters, they are displayed in proximity to some of the most revered pieces of art history. The result is not flattering for Freud, whose paintings appear less self-assured and more filled with doubt than I had previously recognised. Freud himself remarked that he sought inspiration in galleries, using them as “doctors” to examine “situations within paintings” rather than the entire work. Yet, many of the pieces here feel like they need more than just observation—they seem to be in need of major revision.

The show begins with Freud’s early works from the 1940s, where his crude, thick brushstrokes reflect a youthful, somewhat naïve approach. A pivotal moment occurs with Man with a Feather (Self-Portrait) from 1943, where Freud starts to refine his technique, thinning his paint for greater descriptive detail. This transition leads to his most compelling works from the 1940s and 50s, including Girl with a Kitten (1947) and Man with a Thistle (1946), where Freud’s sensitive brushwork creates powerful, often unsettling effects.

However, as the exhibition progresses into the 1960s and beyond, Freud’s work becomes less consistent. The move to thicker paints introduces a sense of heaviness and bluntness, undermining the emotional precision of his earlier pieces. The expressiveness of the brushstrokes in works from the 1960s, such as the portraits of women in fur coats, feels less controlled, and by the later works, the paintings seem overworked, leaving a sense of fragmentation rather than cohesion.

One of the more notable failings of this exhibition is the lack of representation of some of Freud’s finest later works, particularly the portraits of Leigh Bowery and Sue Tilley from the 1990s. These works, which arguably mark the zenith of his artistic career, are represented by only a single painting, And the Bridegroom (1993), which, while brilliant, is hardly enough to demonstrate Freud’s late-period mastery.

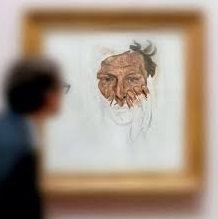

Throughout the exhibition, Freud’s greatest strength lies in his starkness and objectivity. His finest works are those where he refrains from over-narrating or indulging in excessive imagination. Yet, as the show progresses, his tendency to overwork certain paintings detracts from their impact. In many later works, such as Self-Portrait Reflection (2002) and Profile Donegal Man (2008), the paint becomes cloying, interrupting the clarity of his earlier style.

What is perhaps most striking is how Freud’s attempts to align himself with the Old Masters seem to have hindered his creative freedom. His desire to perfect the anatomical details of the human form, particularly the arms and legs, led him to restrict his artistic expression, a theme that is evident throughout the exhibition. The incidental details in some works, such as the torn sofa in Painter and Model (1986-87), are beautifully rendered, but they highlight the contrast between the artist’s skill in these small elements and the unevenness of his broader compositions.

Ultimately, this exhibition leaves me with the impression that Lucian Freud, though undoubtedly fascinating, is far from the genius often ascribed to him. He was a painter of great occasional brilliance, but one whose career was also marked by inconsistency. In attempting to showcase new perspectives, this show inadvertently highlights Freud’s uneven nature as an artist, reminding us that, while occasionally extraordinary, his work often remains decidedly ordinary.

Comments

Hello world!

Pic of the week: Sunset at margate beach

The first day’s journey was through the pink fields

The first day’s journey was through the pink fields

The first day’s journey was through the pink fields